The tools experts use

Ideas to implement

So if you’re ready to jump in, let’s look at some ideas for those in-the-moment situations that make it seem like anger is inevitable. What can we try? What’s the alternative?

Explore the following sections for practical tips and tools.

Tools for emotion regulation

There are a few tools to try for in-the-moment emotion regulation. The first (and easiest) is a specific way of deep breathing that reduces stress. The technique involves taking a double inhale followed by a long exhale. Andrew Huberman explains it in his post Physiological Sigh. If you can take 90 seconds in a moment of anger and try the sigh a couple of times, a lot of the overwhelming feelings will dissipate.

And most of us know that other physiological changes, like going for a walk, taking a bath, having a comforting drink, can help regulate and adjust our emotions in the moment. Keep in mind though that for anger, activities that decrease physiological arousal (calming activities like meditating) are going to be more helpful than activities that increase arousal (like intense exercise or going for a run). But you could always follow up a run or intense cardio with a breathing exercise or meditation to lower your heart rate.

“Anxiety is contagious. Intensity and reactivity only breed more of the same. Calm is also contagious. Nothing is more important than getting a grip on your own reactivity.”

Harriet Lerner

In situations of true emotional overwhelm, these physiological tactics can be a lifeline for stopping ourselves before anger gets out of control. You can explore more ideas at the GoodTherapy blog.

When you have a bit more in the emotional (or physical) tank and want to work more on your emotional regulation for future experiences, explore cognitive reappraisal:

Cognitive reappraisal involves reframing an emotional experience in a different way, or evaluating and analyzing the situation from a different perspective. This can de-escalate emotions, reducing their intensity and duration. The book Behave, by Robert M. Sapolsky, puts it this way:

“Get a bad grade on an exam, and there’s an emotional pull toward ‘I’m stupid’; reappraisal might lead you instead to focus on your not having studied or having had a cold, to decide that the outcome was situational, rather than a function of your unchangeable constitution.”

“Cognitive reappraisal reflects a core fact of psychological life—individuals can play a significant role in shaping their own emotional experience.”

Cognitive Reappraisal, Psychology Today

This type of reframing helps you move from controlled by an emotion to considering a range of inputs and perspectives that are more helpful for moving forward. Susan David explains this perspective, where you consider your emotions but don’t always let them lead your behavior, in her book Emotional Agility. She writes:

“Thoughts and emotions contain information, not directions. Some of the information we act on, some we mark as situations to be watched, and some we treat as nonsense to be pitched into the circular file.”

To try it on yourself, ask questions like these from Psychology Today:

Are any positive outcomes possible from the situation?

Am I grateful for any aspect of the situation?

What did I learn from the experience?

A new way of communicating

Talking is so natural, so necessary. It often feels restrictive and unfair to even try and say something in a different tone or manner than how you feel like saying it. But there’s so much power in what we say and how we say it.

“The tongue has the power of life and death.”

Proverbs 18:21

“Do not let any unwholesome talk come out of your mouths, but only what is helpful for building others up according to their needs, that it may benefit those who listen.”

Ephesians 4:20

And David prayed:

“Set a guard, O Lord, over my mouth; keep watch over the door of my lips”

Psalms 141:3

I remember when I was first married. I kind of thought that the ideal relationship was one where you could tell the other person everything, share everything, not hold anything back. But after a little while I saw that with your spouse, you affect each other so much, so deeply (especially with our personalities; we’re both pretty sensitive), that a marriage relationship is less about giving free reign to what you want to say, and more about finding a way to express yourself fully while also considering the other person’s needs, feelings, vulnerabilities…It’s harder, but better in the end.

-Anonymous contributor

As a foundational or grounding principal, we know we need to communicate in a way that:

Helps build others up

Meets others according to their needs

Benefits those who listen

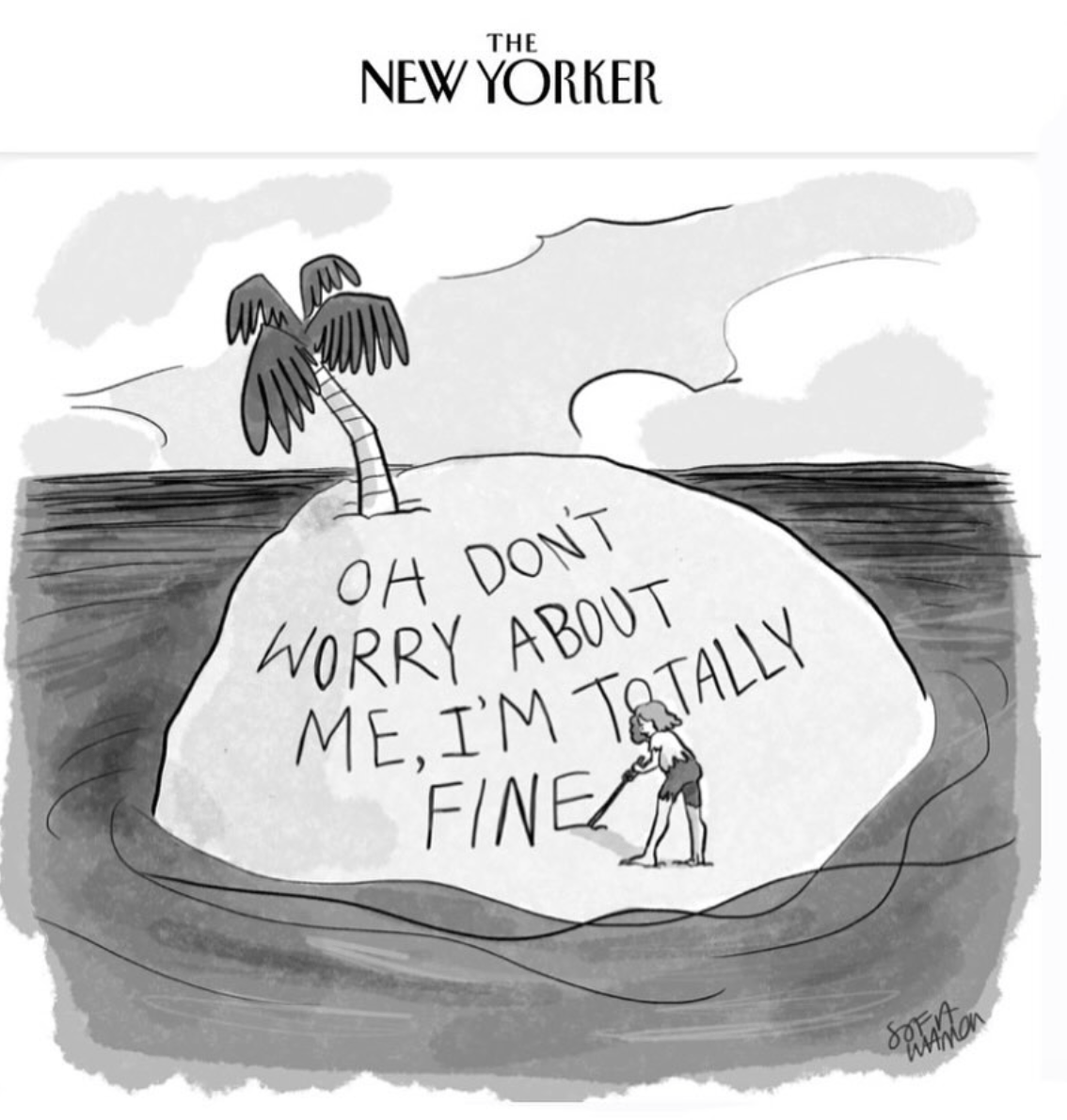

At the same time, we still need to be able to address our own needs, share our struggles, make our opinions known. It doesn’t do any good to keep a tight-lipped silence where resentment and bitterness lay just beneath the surface.

So we’re working toward communication that moves from:

1

Closed off

More open

2

Cryptic

More straightforward

3

Spiteful

More respectful

Consider the following tactics and see what works for you.

1

Less closed off → more open

Acknowledge your emotions early

Although it feels oversimplified and obvious, we can’t expect others to know what we need or how we feel unless we tell them. It’s easy to ignore smaller feelings of irritation or disappointment and just mutter something under your breath rather than addressing it. You might wish your spouse would read your mind (or your body language) and know exactly what’s wrong and how to fix it. But most of the time that just leads to more resentment.

Acknowledging feelings while they’re still small can save a lot of pain and bigger blow-ups later. A dad’s story in How to Talk So Little Kids Will Listen shows a good example of this:

“I was ironing a shirt when Jamie asked me to help him make a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Normally I would have stopped ironing to do it. I’d have to unplug the iron and put it away so Kara couldn’t touch it. But then I realized I didn’t want to do that, so I told him, ‘I’ll get frustrated if I don’t finish this shirt first. I can help you as soon as I finish ironing the sleeves.’ Jamie said, ‘Okay, Dad,’ and then he stuck around to watch me iron. I would never have thought to tell him my feelings before this class. It’s so strange to me that I didn’t learn to say things like ‘I’m frustrated’ until I was thirty-four years old, and my son already knows that at four. He’s way ahead of me!”

However, it can be easy to slide from trying to address issues early into going a bit overboard on complaining and criticizing. It matters a lot how you bring up these issues and your motivation behind it. There’s a big difference between wanting to “correct” a person versus sharing your feelings. One strategy to try before jumping in on a complaint is what Gretchen Rubin terms making the positive argument.

Kathleen Robinson describes how she puts this into practice in one of her Substack articles about parenting and dealing with irritability:

“If I am thinking something negative, I can essentially argue with myself and make a positive case for it. The idea is to come to a more balanced outlook… If we are willing to be truly honest with ourselves, I think this exercise can be uniquely effective because it removes the defensiveness or tendency to justify because we are arguing with ourselves… The best thing about this exercise, though, is that what can begin as a criticism or negativity in your heart can turn into a love letter.”

Making it a priority to share your needs, expectations, and desires before they become resentments can go a long way in stopping anger before it starts.

“But by and by… she began to miss John… She would not ask him to stay at home, but felt injured because he did not know that she wanted him without being told, entirely forgetting the many evenings he had waited for her in vain.” Little Women

What’s one feeling or expectation you can share today with your spouse or child?

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

2

Less cryptic → more straightforward

Say it plain

The next step beyond just saying something early is, of course, how you say it. This section and the next two (here and here) go into more detail about ways to communicate effectively while still being able to share your genuine feelings.

We could have called this section “The surprising benefits of stating the obvious” because there’s something a bit magical about neutral (rather than emotionally charged), direct (rather than passive), and descriptive (rather than vague) language. But how often do we use passive-aggressive or cryptic language instead of transparent communication?

“Clear is kind. Unclear is unkind.” Brene Brown, Dare to Lead

A note about sarcasm:

Sometimes we use sarcasm and think it’s playful and fun. But be careful that you’re not using sarcasm to hide real issues that need addressing. Brene Brown’s book Atlas of the Heart offers a good self-check for sarcasm: “Are you dressing something up in humor that actually requires clarity and honesty?"

Neutral, direct, and descriptive language can feel like stating the obvious because (1) you’re often just repeating back what you saw someone do or heard someone say, or (2) you’re describing how you feel and what you want, which can at times feel like it should be obvious (see previous section).

This conflict resolution resource has many examples of non-judgemental phrases that can help get to the heart of real and difficult issues or disagreements without putting the other person into defense mode.

Especially with kids, it’s so easy to pass judgment on what they get upset about, what they like or don’t like, etc. And those judgments don’t end up helping them behave better or deal with their emotions more effectively. A lot of time a neutral, descriptive acknowledgment can go a long way toward helping them handle their emotions and be open to feedback.

Some examples specifically for kids:

Language that makes a judgment | Neutral, descriptive language | |

[Child crying for unknown reason] | “There’s no need to cry right now.” | “I see that you’re upset.” |

[Child pulled the cheese off her pizza slice] | “But the cheese on pizza is the best part!” | “Cheese doesn’t taste good to you right now.” |

[Child wanting to show parent a jump] | “That was amazing!” | “You jumped with both feet off the ground for the first time!” |

[Child left her stuffed animal at home on accident] | “It’s okay” | “It looks like you’re feeling disappointed that your stuffie was left at home.” |

[Child messes up something the parent knows they can do] | “You can do better.” | “I would love to see you explore/try…” |

For more examples, How to Talk So Little Kids Will Listen has a whole chapter on it (chapter 4).

What’s so great about neutral, direct, and descriptive language? This kind of communication:

helps keep a conversation from escalating into anger/rage

allows others to relax, open up, share more

enables others to feel acknowledged

is one antidote to over-praise (as in, praise that ends up making kids less likely to try new things and take risks; see Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck for details)

Often, kids (and adults) already know or can figure out what they did well or what went wrong. By describing, rather than evaluating for them, we give them more space to think critically. And we keep from weighing the situation down with immediate criticism, so they can experience, acknowledge, and process their emotions, without jumping straight into defensiveness.

To reassure you: this doesn’t mean you need to change any rules or let anyone get away with anything. You can still enforce rules and maintain boundaries while using neutral language.

Give yourself a bit of a challenge and try to pay attention to the number of value judgments you make in a day. And see what you can do to turn some of them into neutral statements.

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

3

Less spiteful → more respectful

Remove the venom

Sometimes we can try and communicate early and calmly with descriptive and neutral language, before a lot of rage has built up. And that can help the pressure release and resolve small things before they get big.

But what about when the emotions are already more intense? It doesn’t always work to say things neutrally, especially in tense and charged situations, or when you’re emotionally fried. We need a way to express ourselves fully without poisoning the air and the people around us. We need to remove the venom from our speech.

In his book “Nonviolent Communication,” Dr. Marshall Rosenberg explained what he did to share his intense feelings without hurting his son in the process:

“I recall spending three days mediating between two gangs that had been killing each other off. One gang called themselves Black Egyptians; the other, the East St. Louis Police Department. The score was two to one—a total of three dead within a month. After three tense days trying to bring these groups together to hear each other and resolve their differences, I was driving home and thinking how I never wanted to be in the middle of a conflict again for the rest of my life. The first thing I saw when I walked through the back door was my children entangled in a fight. I had no energy to empathize with them so I screamed nonviolently: ‘Hey, I’m in a lot of pain! Right now I really do not want to deal with your fighting! I just want some peace and quiet!’ My older son, then nine, stopped short, looked at me, and asked, ‘Do you want to talk about it?’”

The idea behind “scream nonviolently” is that if you express your pain (even intense pain) without attacking the other person, it’s much easier for the other person to respond with care and compassion. They don’t jump into defending themselves or protecting themselves. But this requires a lot of vulnerability on your part, the one feeling pain, and will probably take a lot of practice for those who aren’t used to it (most everyone).

The authors of How to Talk So Little Kids Will Listen have some similar suggestions:

“Say it with a word. When I’m driven into a frenzy by dawdling kids (and my gentler tools of playfulness and offering choices to get them into the car have failed) I yell, ‘CAR!!!’ with all my frustration packed into that word. Chances are the word car, even delivered at top volume, will not cause lasting damage to the psyche.

If one word is not enough, you can direct your fury into giving information. You can roar, ‘BROTHERS ARE NOT FOR KICKING!!!’

You can express your feelings strongly. Use the word I instead of you. ‘I GET VERY UPSET WHEN I SEE A BABY BEING PINCHED!!!”

You can describe what you see. ‘I see people getting hurt!!!’

You can take action. ‘I can’t allow sand throwing! WE ARE LEAVING!!!’

None of these words wound. They don’t tell a child he is mean or worthless or unloved. They do let him know that his parent is past all patience. And they model a healthy way to express anger and frustration without an attack.

Of course, being yelled at by a furious parent can be an upsetting experience in itself. That can’t be the end of the story. It’s important to reconnect after the intensity of anger has abated. Our kids need to know there is a way back into our good graces and a better way to go forward. That can start with acknowledging feelings all around. ‘That was no fun. You didn’t like getting yelled at. And I was really mad about___ (insert your gripe here)’”.

How do you feel about the idea of expressing intense emotions in a “nonviolent” way? What from this section do you want to try?

_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________

Get good at reconciliation

No matter how much and what we try, we will at times fail. What then? All is not lost. Those times of failure are important opportunities to practice being vulnerable, admitting mistakes, and restoring bonds.

Psychologist and parenting influencer Dr. Becky calls this “repair.” In her TED talk on the topic, she says:

“Repair is the act of going back to a moment of disconnection. Taking responsibility for your behavior and acknowledging the impact it had on another. And I want to differentiate a repair from an apology, because when an apology often looks to shut a conversation down—‘Hey, I’m sorry I yelled. Can we move on now?’—a good repair opens one up.”

Throughout her talk she has many examples to try of what repair looks like, particularly between parents and children. The Gottman Institute has an article with some additional insights into spousal relationship repair.

And what about when our kids (or others) fail us? We often require children to adjust themselves to our requirements and expectations. And rightly so. We need to be the ones to explain the rules and teach them how to live up to our and God’s standards. We expect them to conform to our ways. Sometimes, however, this can go too far to the extreme of expecting a lot from them and letting ourselves off the hook.

“…feelings like disappointment, embarrassment, irritation, resentment, anger, jealousy, and fear, instead of being bad news, are actually very clear moments that teach us where it is that we’re holding back. They teach us to perk up and lean in when we feel we’d rather collapse and back away. They’re like messengers that show us, with terrifying clarity, exactly where we’re stuck.” Pema Chödrön

We can’t expect them to have the same level of emotional maturity as we do, or to build emotional maturity without our help in tough moments. We need to show them what repair and reconciliation looks like. We need to make it clear that there is a path back to a strong and close relationship when they fail or disappoint us.

God and Christ showed us this by their example of love even when we were (and are) falling short (Romans 5:8). God didn't wait for us to turn things around before forgiveness was granted. He showed us what love is before we were ready or able to start living His way. He sacrificed Himself for us without any guarantee that we would do anything in return.

“God…through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation.”

II Corinthians 5:18-19

Some practical ways we can reflect a little bit of God’s reconciliation to our kids and others (when we fail or when they fail us):

Get rid of the silent treatment (a way of punishment that cuts off access to reconciliation)

Be the one to broach a difficult conversation

Be willing to take responsibility and apologize for mistakes

Be willing to be held accountable

React with vulnerability and compassion instead of animosity when someone hurts us

“The best way to help a child ‘get over it’ is to help him go through it.”

Joanna Faber and Julie King, How to Talk So Little Kids Will Listen

Model empathy and work on being “slow to anger”

Our children copy what we do. We see this when they repeat some phrase in our exact tone of voice. Or when they make a certain facial expression that seems beyond their age. But it’s easy to overlook just how much they are forming their understanding of the world and how to be from what we do and how we react to things. As the authors say in their book Raising Resilient and Compassionate Children:

“Children cannot be if they cannot see.”

How can we expect our children to be patient, compassionate, and kind if we don't show them the model on a daily basis? God does give us that example, with some of his core attributes being compassionate and slow to anger.

So what are some practical ways we can model empathy, compassion, and being slow to anger?

Practice giving them the empathetic, compassionate, and kind words that they may not have yet. This happens when you:

“Compassion is the daily practice of recognizing and accepting our shared humanity so that we treat ourselves and others with loving-kindness, and we take action in the face of suffering.” Brene Brown, Atlas of the Heart

Verbalize things from their point of view

Acknowledge what you think they are feeling and why

Reframe and give alternatives when they use harsh or hurtful language

This kind of language is kinder and gentler, but it also requires more specificity about the emotions involved. (It’s easy to respond with something like, “That’s not nice!” But that isn’t specific about what was wrong and doesn’t give an alternative.) It’s helpful to prompt and guide the child to think about what specifically they are struggling with and feeling, rather than verbally attacking whatever upsets them. This helps build skills in empathy.

Watch this video from Conscious Discipline for more examples and scripts.

All this goes back to remembering our overarching goal, with our children, or with any relationship. It can be easy to feel your emotions are justified or valid. But do our actions and behaviors and words actually promote reconciliation, learning, growth? Or do they just punish and assuage our own feelings?

It might require some deep thought about what you’re truly wanting in the moment: just some peace and quiet? To avoid embarrassment? To vent your own rage? And not let those feelings drive your response.

“...put off all such things as anger, rage, malice, slander, abusive language from your mouth…clothe yourselves with a heart of mercy, kindness, humility, gentleness, and patience…”

Colossians 3:8, 12

Pastor Gary Petty, in his sermon Love Is Not Provoked, explains the danger of our children potentially learning that the purpose of family is just to keep mom and dad from losing their temper, instead of teaching them the difference between right and wrong. If parents don’t control their anger, their children can become angry adults, missing the point of what right and wrong really is. The most important thing becomes keeping mom and dad from getting mad.

“...parents just have to be good enough. They have to provide their kids with stable and predictable rhythms. They need to be able to fall in tune with their kids’ needs, combining warmth and discipline. They need to establish the secure emotional bonds that kids can fall back upon in the face of stress. They need to be there to provide living examples of how to cope with the problems of the world so that their children can develop unconscious models in their heads.”

David Brooks, The Social Animal

Remind yourself that there’s more at stake. We’re the role models for those looking up to us. We must work to model godly characteristics. If not, our children will have a much harder time trying to develop those characteristics on their own.

Try therapy

We all have ups and downs in our emotional lives. (As we saw, so does God.) But if you find yourself constantly angry at small things, or sad and gloomy most of the time on most days, you might need to look beyond the tools in this project.

Don’t underestimate the power of your emotions and moods. Consistent or lingering anxiety, depression, etc., can have significant and lasting effects on other areas of your life. In her book Philosophy of Emotion, Christine Tappolet explains:

“…there is a marked tendency to make mood-congruent judgments [judgments aligned with our moods], and [moods] also have an impact on attentional processes, memory tasks, and categorization tasks.”

In other words, it’s much easier to make decisions that go along with our moods than go against our moods. If you are constantly in a very negative mood, it’s going to be much harder to act in ways that reflect love, peace, gentleness, and mercy.

So don’t wait to get help. You may feel like your problems aren’t big enough for seeing a therapist, or you might feel uncomfortable sharing personal and family issues with someone you don’t know. But being able to work through challenges with the support of trained professionals can really speed up the process of growth.

“Digestive disorders, heart disease, obesity and chronic pain are just a few of the potential physical effects of anxiety and depression, especially those left untreated. Other health problems associated with depression and anxiety include substance use disorders, respiratory illnesses and thyroid issues." Advanced Psychiatry Associates, The Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Your Physical Health

It’s also important to realize that if you have something that keeps coming back up over and over again in a relationship and that is a trigger for anger, you’ll need to deal with the actual issue, which a therapist or counselor can help do more effectively often than not. If you’re only ever trying to manage anger outbursts, but don’t deal with the underlying issue, you’re just addressing the symptoms and not the cause.

Speaking with a therapist can help you:

Feel acknowledged and heard (which helps offload some of the need we have for our family and friends to do that for us)

Hear a different perspective from a non–emotionally invested third party

Hear a different model for how you could talk to yourself (understanding and changing the negative voice in your head)

Be taught new tools and skills for managing and processing difficult experiences and emotions

Be reassured that you can share your feelings without overwhelming the person you’re talking to

There are many different kinds of therapy, and different therapists have different styles as well. You can read about some of the main types of therapy here. It’s normal and expected to explore a bit and find a style and a person who works well for you.

Locate a counselor:

Go for joy and embrace meaning

Sometimes it can feel like our anger is our strength. Unleashing our anger can sometimes be effective in making people do what we want; it can get people to take us seriously. But Nehemiah 8:10 says,

“...the joy of the Lord is my strength.”

And God’s own strength stems from His goodness, joy, and love (Psalm 145:5-7).

How can we find the strength that comes from a joy-filled, meaningful life? Rather than a life powered by anger?

Take a look at this clip (34:44 - 40:00) from a speech on dopamine:

In this clip, Kayleen Schreiber discusses a tool for dealing with difficult emotions in the moment.

As she explains, it’s easy to get into this cycle:

Dopamine trigger

More sensitive to irritations

Ignore feelings

Use phone/social media for more dopamine…

So dopamine can start to short-circuit our paths to actual meaning and true joy by instead giving us a temporary good feeling that dissipates quickly, leaving us unsatisfied again. And over time this actually results in increased emotional and physical pain. As Anna Lembke summarizes in Dopamine Nation,

“With prolonged and repeated exposure to pleasurable stimuli [including social media], our capacity to tolerate pain decreases, and our threshold for experiencing pleasure increases.”

Kayleen suggests changing that cycle:

Remove the dopamine trigger

Observe feelings

Address underlying need (if possible)

Turn attention outward

By allowing yourself to temporarily feel and acknowledge the negative feelings, you trigger your brain to make other chemicals that naturally make you feel better. Then, instead of constantly distracting yourself from your irritation or anger, you can turn your attention to something else more productive and positive.

After honestly assessing what’s going on inside (what specific emotion am I feeling and why), turn your attention outward. When we can’t solve our problems or wish away our emotions, we can put some energy and attention on others. Either by being grateful for blessings, observant of our environment, or working to serve others. These all help because they start to shift your perspective. This in itself lessens the intensity of whatever emotion you’re feeling. And it can be the start of using an otherwise just irritating and frustrating incident into an opportunity to address a need, share a vulnerable truth, or learn something about yourself.

“We need happy moments and happiness in our lives; however, I’m growing more convinced that the pursuit of happiness may get in the way of deeper, more meaningful experiences like joy and gratitude. I know, from the research and my experiences, that when it comes to parenting, what makes children happy in the moment is not always what leads them to developing deeper joy, grounded confidence, and meaningful connection.” Brené Brown, Atlas of the Heart

We can’t force ourselves to like something we just don’t like (especially in the moment). Trying to get yourself to love playing house with your kids for the millionth day in a row is probably not going to do much for you. But reminding yourself things like “I have a family and that’s a blessing,” or trying to be more observant of a new skill your child is developing, or appreciating the nature outside your window, can help shift your perspective to something bigger than the present infuriating moment. (This goes back to the reappraisal approach to emotion regulation.) As Kayleen mentions, though, it takes time and faith—and practice.

For more details on this process and strategy, check out Dopamine Nation. If you feel like you aren’t making any progress trying to shift your mindset, it might be a helpful first step to start a gratitude journal. Lots has been written about this idea, and evidence shows that making a habit of writing down 2-3 things you are grateful for each day can have a positive effect on mental health and help with symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Those reminders that keep things in perspective can go a long way toward embracing the good and bad moments, since they’re all part of what makes a rich and meaningful life. And a life of meaning is a powerful motivator to do right and live better. As David J. Lieberman says in his book Never Get Angry Again:

“I will wake tomorrow and be glad to open the curtains, and drink coffee and think of those I love who are near and far. And then I will get back to work, the real deep work that goes on every day." Fergal Keane, 'I spent 30 years searching for secret to happiness - the answer isn't what I thought'

“When we live full, robust lives, we tend to embrace our values and beliefs—whatever brings meaning into our lives. Known as the mortality salience hypothesis, it promotes self-regulation. Alternatively, if we already have one foot in the Land of Escapism, we are inclined to pacify our fears by further indulging ourselves–in anything from chocolate to extravagant vacations.”

So take stock of your life. Don’t try to pretend to like things you really don’t, but do keep bringing yourself back to the bigger picture where God is for us, we are blessed, and we still have time in our lives for things to change and keep improving.

What have you found that works for you to experience more joy and less anger?

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

If you’d like to join a community of like-minded believers and intentional parents, please join our intentional parents group: The Grove!

Share this site: